Research

Elevational Generalism

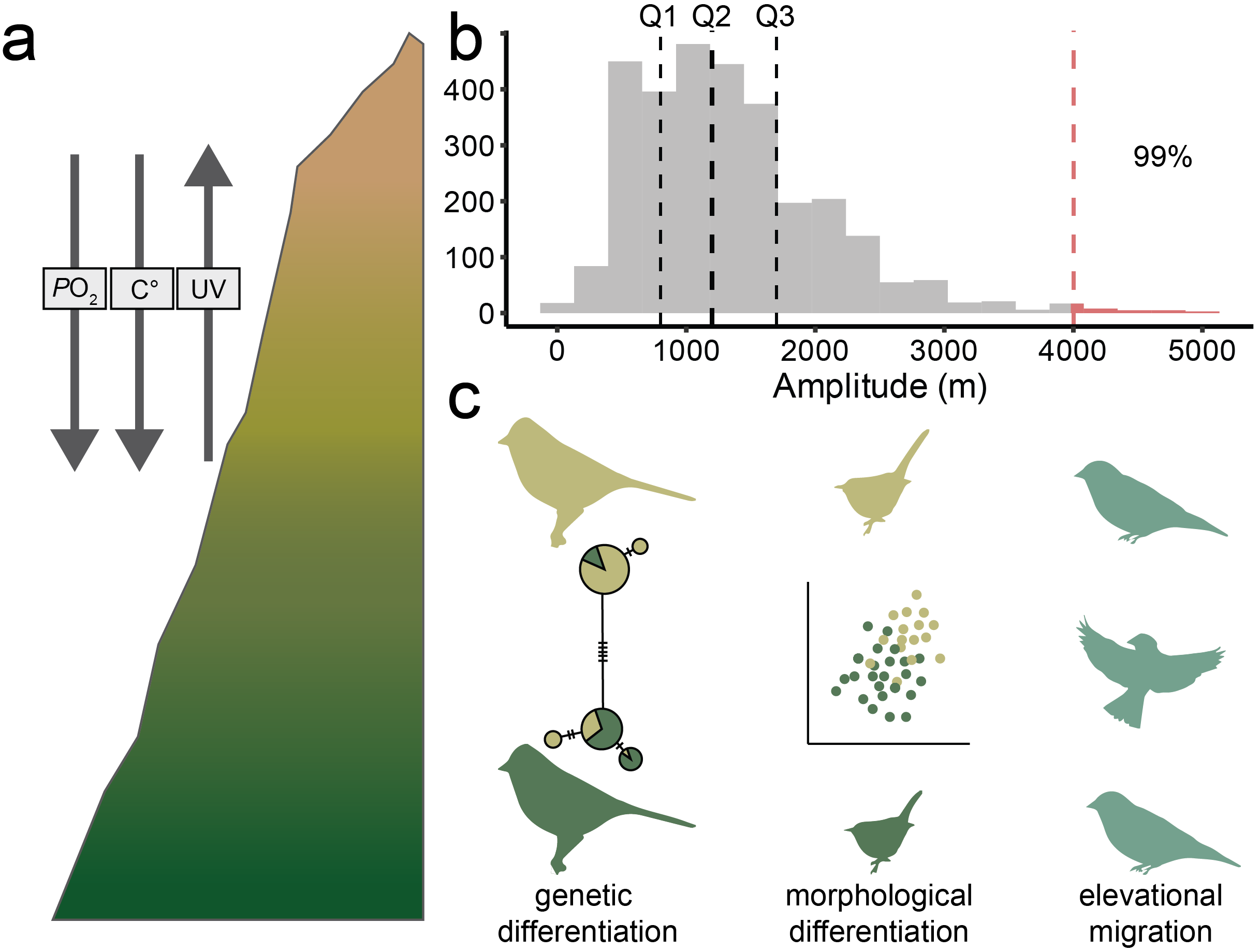

Most Andean birds inhabit narrow elevational

ranges thought to be set by a combination of biological and environmental factors. Very few species

inhabit more than 3,000 meters in

elevation. Those that do must compensate for large shifts in

temperature, UV exposure, and the partial pressure of oxygen. Are these exceptional species

physiologically adapting in the face of gene flow, or are plastic and behavioral

responses, allowing them to persist across diverse environmental conditions and preventing them from

specializing on narrower elevation zones?

In Gadek et al. 2017 I found that elevational generalists are either in the process of

diversifying, expanding across

the gradient, or undertaking seasonal or resource-pulse-driven elevational migration, and that

elevational generalism is an unstable and transient condition.

Conceptual figure illustrating the three main mechanisms at play in maintaining or eroding elevational generalist's wide ranges.

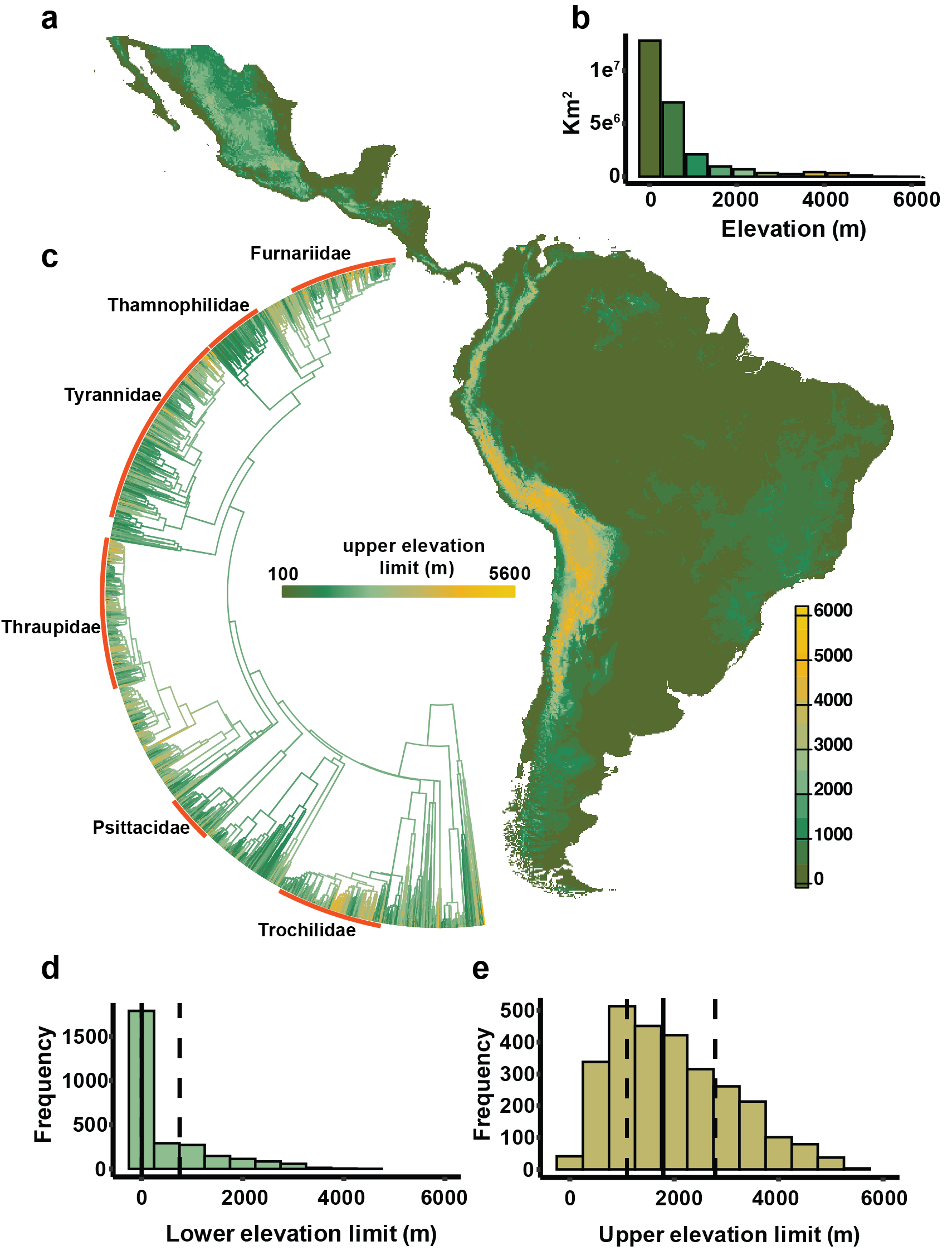

Evolution of Elevational Ranges

The evolutionary history of neotropical birds has

undoubtedly been influenced by

Andean uplift, leaving us with current patterns of high diversity and endemism in and around the

Andes. These species' modern elevational ranges represent cumulative histories of expansions and contractions in mountains over evolutionary timescales.

To anticipate how elevational ranges will respond to climate change in the near term, we must understand how they evolved. To this end, I ask: How did elevational ranges

form and change over time? How rapidly have they shifted? Are upward and downward shifts

symmetrically distributed across the

elevation gradient? And how do patterns of range evolution differ among clades?

This work is being done in collaboration

with Eli Stone and Selina

Bauernfeind.

Study context describing elevational ranges of neotropical birds. (a) map of the study region with an elevation model at 30-second resolution. (b) Land area across the study area in 500-m elevation bins. (c) Upper elevation limits of 2,774 species in this study mapped onto a phylogeny (birdtree.org); avian families of over 100 species are highlighted in red. (d) Lower elevation limits and (e) upper elevation limits of the 2,774 species with median (solid bar) and 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed bars).

Plasticity and Adaptation During Extreme Elevational Transitions

Plastic responses to acute changes in elevation are

well documented and shared across many vertebrates.

Similarly, genetic adaptation to high-elevation environments often acts on predictable physiological

pathways. But how do these processes interact, and how do they transition between one another?

To ask these questions, we sampled the entire Peruvian range of two co-distributed marsh birds (

Phleocryptes melanops & Tachuris

rubrigastra). These birds have disjunct elevational ranges,

inhabiting coastal marshes at sea level and high-elevation marshes above 4000 meters. Are the high

elevation populations adapted(ing) to the dramatically lower oxygen availability? Or has gene flow

and recent colonization failed to suppress short-term acclimatization responses? This work is in

collaboration with Jessie

Williamson.

Photograph of Many-colored Rush Tyrant (Tachuris rubrigastra) from Puerto Viejo, Peru, in 2016.

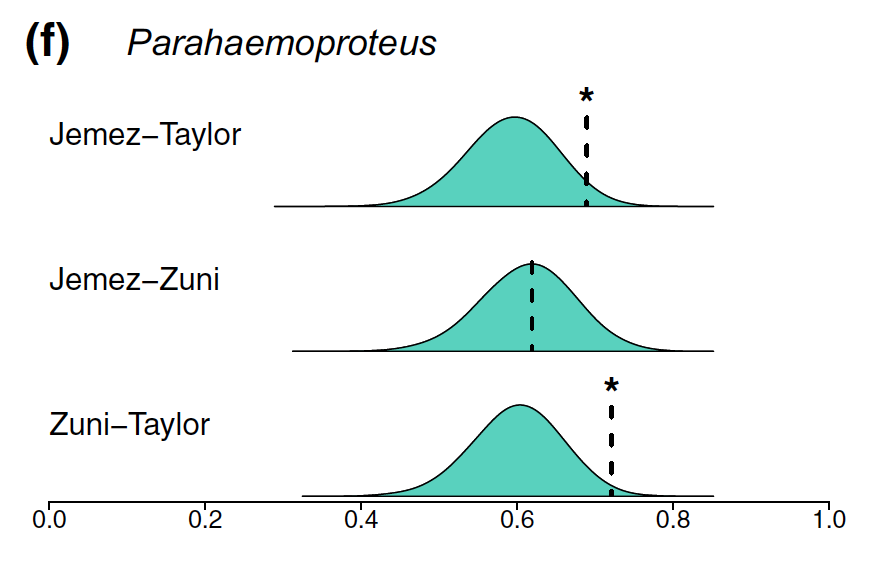

Malaria in Sky Islands

Avian malaria is a widespread chronic disease of birds

caused

by

multiple

Apicomplexan organisms.

To understand how host and pathogen communities vary across the landscape, we surveyed birds and

parasite

communities among

Southwestern sky islands and simulated null communities to compare against empirical data.

We

found that parasite communities differed between sky islands relative to null community models,

suggesting idiosyncratic colonization and extirpation dynamics. This work is in collaboration with Christopher

Witt,

Lisa Barrow, Jessie Williamson, Selina

Bauernfeind, and Rosario

Marroquin-Flores.

Figure modified from Barrow et al. 2021 showing observed (dashed lines) and expected Jaccard Index values. Expected values obtained from 10,000 randomly simulated communities. Illustrates how observed communities in two "sky islands" differ from expectations.

Tracheal Evolution in Sandhill Cranes

The sandhill crane (Grus canadensis ) is among the few bird species that exhibit tracheal elongation. Within this species, there is substantial size dimorphism between subspecies. Jones & Witt 2014 found that the smaller subspecies that undertake longer distance migrations had proportionally longer trachea hypothesized to make smaller birds sound bigger. I am interested in assessing the symmetry and strength of sexual dimorphism within sandhill cranes.

Photo of sandhill crane trachea coiled within the bird's sternum.

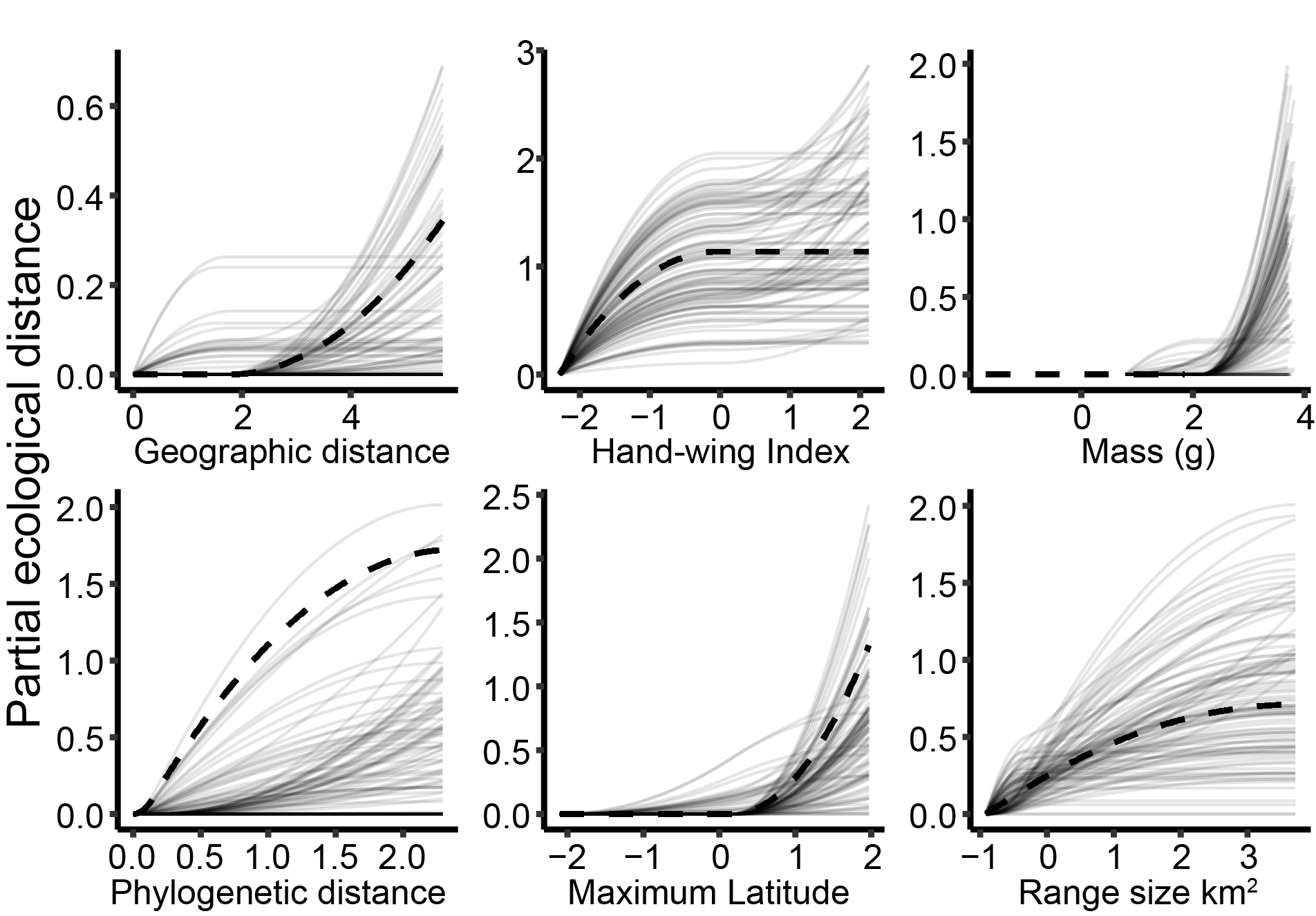

Evolutionary and ecological drivers of microbe-host associations in the lung mycobiomes of birds

Microbiomes are being published at a rapid pace. Yet

wild

bird microbiomes and specifically their fungal components

(mycobiomes) are largely undescribed. Furthermore, how microbiomes are structured by phylogenetic, geographic, and life history traits

remains understudied.

Baseline knowledge of the makeup of these communities and factors that affect their assembly and

maintenance holds important implications for disease ecology, public health, and large-scale

coevolutionary processes.

We are describing the first lung mycobiomes of birds

and modeling the associations of phylogeny, morphology, and ecology with lung fungal communities. This

project is in collaboration with Paris

Hamm & Michael

Mann utilizing samples collected and stored in the Museum of Southwestern Biology.

Global (dashed lines) and subsampled (solid lines) generalized dissimilarity models showing geographic, morphological, and phylogenetic predictors of fungal community dissimilarity. Figure shows (height of lines) that phylogenetic distance, hand-wing index, and maximum latitude of bird hosts explain the most dissimilarity among lung fungal communities